Celebrating the world’s first-ever Ta Wik’ a Ta Rē Moriori

Across Rēkohu, mainland Aotearoa and beyond, communities came together to celebrate ta rē Moriori with houkawe (pride), curiosity, and ka koa (joy). It was inspiring to see our language embraced in so many spaces, by so many people, in so many different ways.

Across Rēkohu, mainland Aotearoa and beyond, communities came together to celebrate ta rē Moriori with houkawe (pride), curiosity, and ka koa (joy). It was inspiring to see our language embraced in so many spaces, by so many people, in so many different ways.

Here on Rēkohu, we began the wik’ in the best possible way, with morning rongo and karakī at Kōpinga Marae, before welcoming our rangata matua in for a beautiful shared kei.

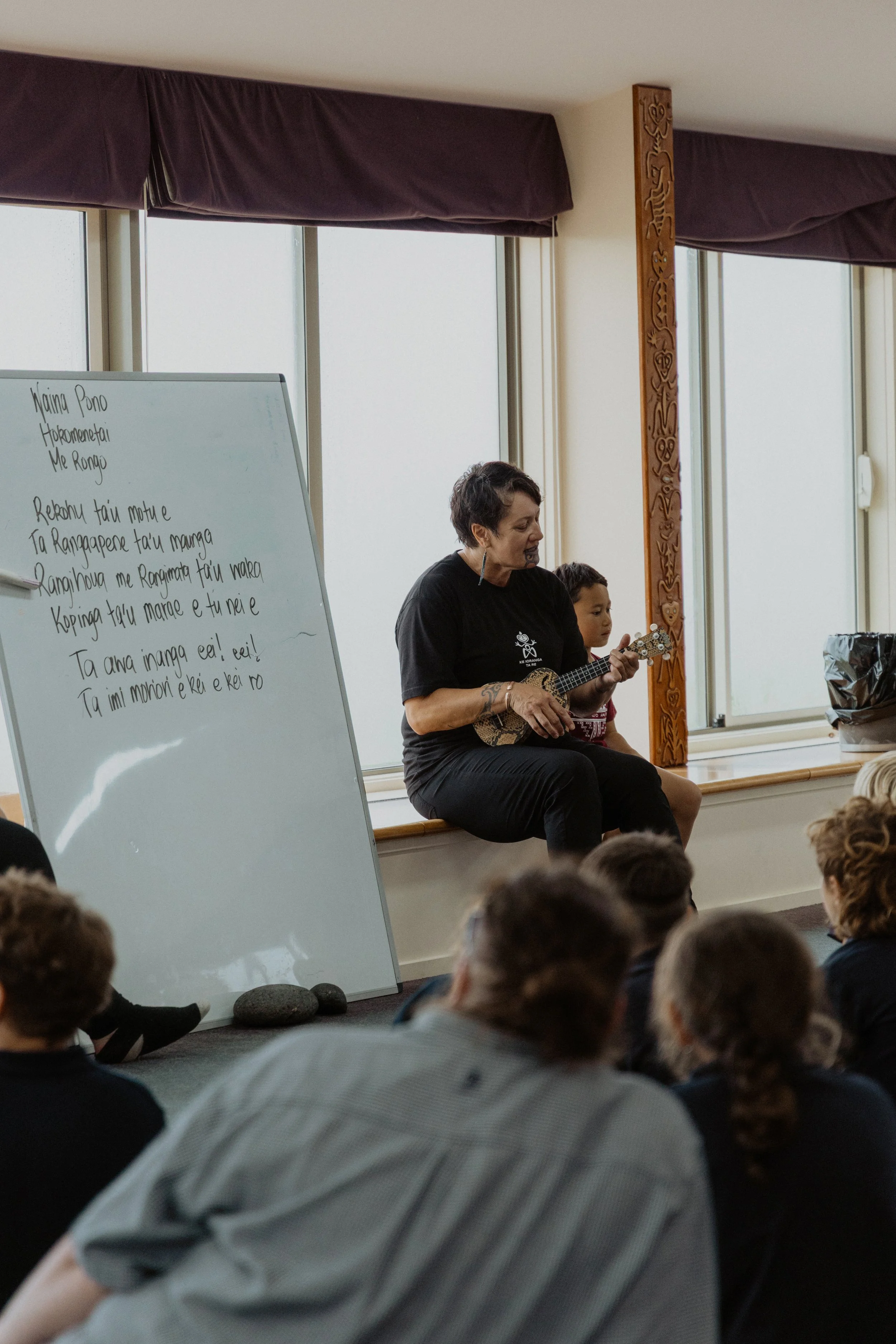

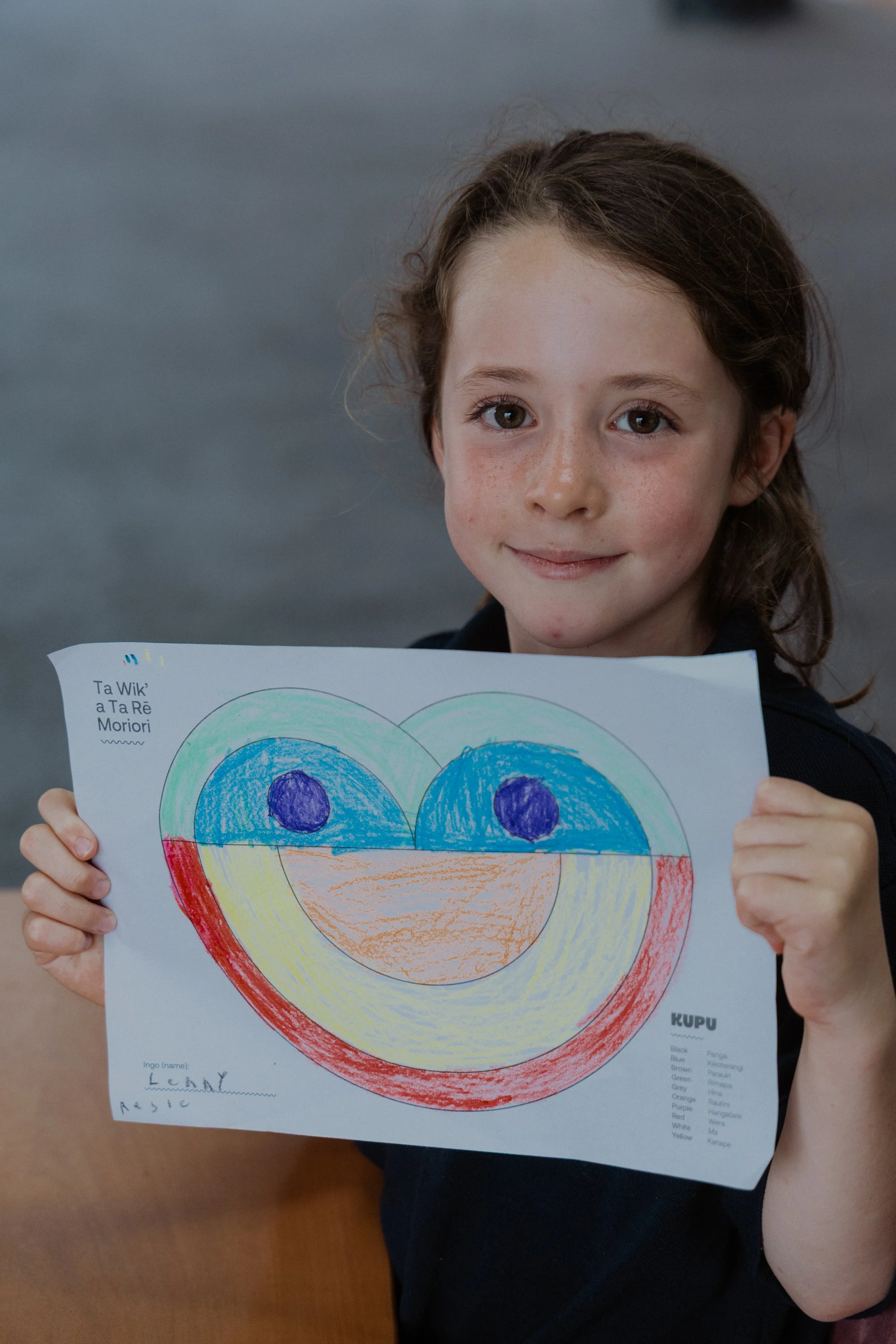

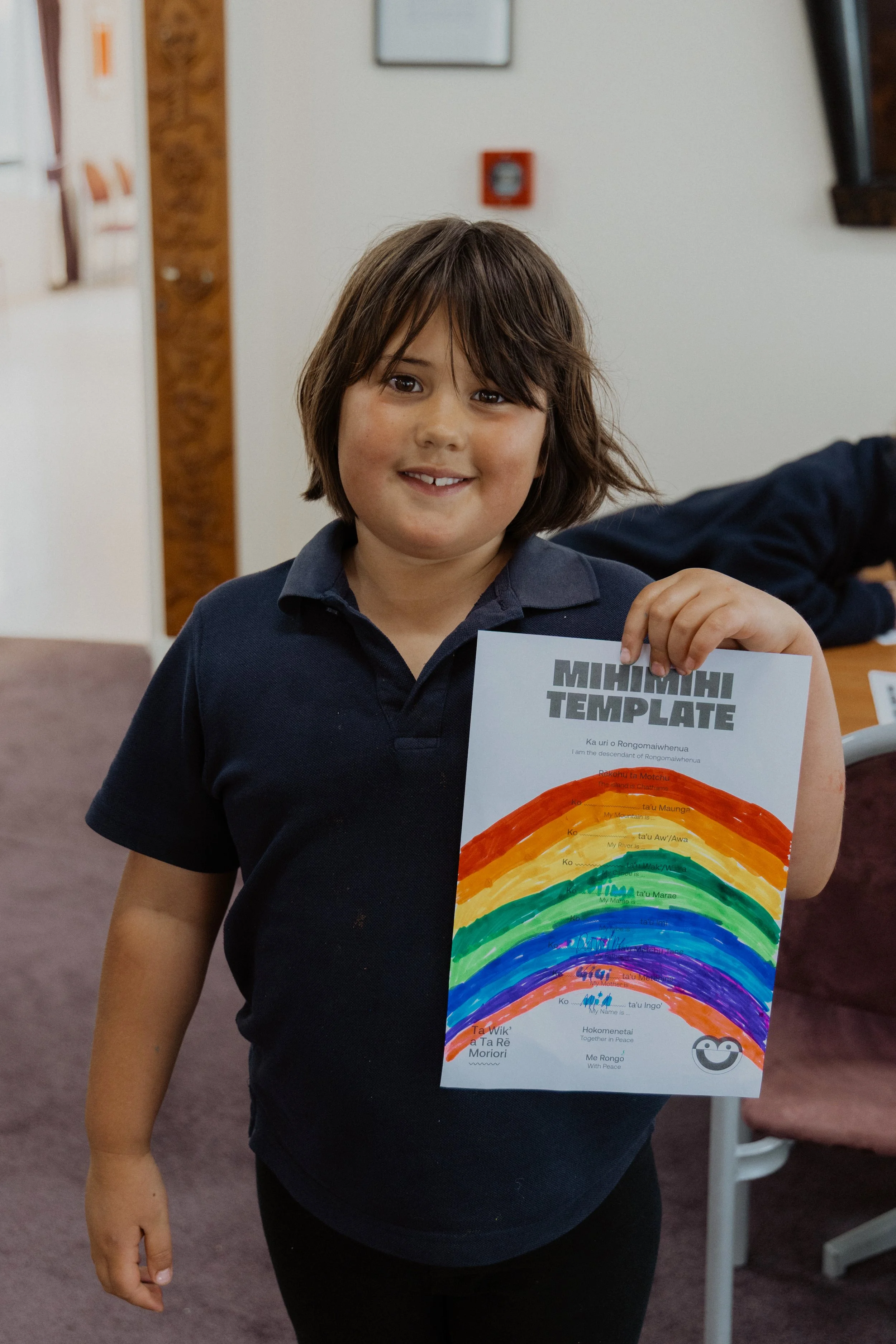

On teru ra (day two), Te One School brought wonderful energy to Kōpinga. Students enjoyed rongo with Tiriana Smith, followed by language activities, colouring pages, delicious kei, and an ice cream to finish.

Toru ra (day three) saw our operations team in Kaingaroa supporting the local inter-school cross country, where ta rē Moriori was proudly on display. Kaingaroa School truly championed the tchipangǎ, with certificates and signs in ta rē Moriori.

On tewha ra (day four), our smallest tchimirik’ filled Kōpinga Marae with laughter, messy play, and rongo in ta rē Moriori. Our timiti were also treated to a special tupukapuka reading with Kate Preece and her trilingual children’s books.

To keep the momentum going on terima ra (day five), athletics day got an exciting upgrade. Our Ta Wik’ a Ta Rē Moriori tees finally arrived after weeks of Rēkohu misty-sun delays. Every tchimirik’ received a fresh tee and a kete miheke (taumaha to Te Mātāwai for the totes), and it was takina seeing them worn proudly around the track.

Teono ra (day six) brought sunshine, slip ’n’ slides, and shared kei to Kōpinga. Our final in-person celebration captured the mouri of Ta Wik’ a Ta Rē Moriori: hokomenetai, iaroha, and coming together to keep our rē alive.

Throughout the wik’, we shared online resources that made it easy for people to get involved, sparking conversations and creating moments of connection in homes, schools, and workplaces.

One of the most powerful highlights was seeing ta rē Moriori celebrated in public spaces and national media. From presentations and talks to media interviews, hearing our language spoken proudly and confidently honoured our karāpuna and affirmed ta rē Moriori as a living, thriving miheke. We are also deeply proud of those who hosted wānanga across mainland Aotearoa, giving our off-island hūnau meaningful opportunities to connect and learn together.

This wik’ was a continuation of the ongoing mahi happening to revitalise ta rē Moriori. Every kupu spoken, every post shared, and every conversation started helps build momentum. Ta Wik’ a Ta Rē Moriori showed what is possible when we come together with positivity and purpose.

To everyone who participated, shared, taught, learned, posted, wore their tees, attended events, or quietly practised at home: taumaha. Your support keeps our rē strong and our culture visible.

We can’t wait to build on this energy in 2026.

If you’d like to celebrate Ta Wik’ a Ta Rē Moriori, we have some great resources available which you can access here.

The Rangihoua: A Moriori Waka Miheke

The discovery of the Rangihoua waka is one of the most significant cultural findings for Moriori. Resting within a protected archeological landscape, this waka is a sacred link to our karāpuna.

The waka was uncovered at the mouth of the Rangihoua Stream on the northern coast of Rēkohu. The discovery sits within a wider Moriori cultural landscape known as Site 100, an area rich with middens and wāhi tchap’. This coastline holds special statutory protection for Moriori, recognising its deep cultural significance.

For Moriori, it is no surprise the waka was found at Rangihoua stream. Our karāpuna named this place and those names carry memories. Our oral traditions tell of early Pacific voyaging, settlement on Rēkohu and Rangihaute, and the arrival of the Rangimata and Rangihoua waka. Archaeological work now supports those kōrer', aligning with traditions that place the Rangihoua and Rangimata voyage around 800 years ago.

The waka’s size, construction, and carved elements reflect Moriori knowledge, artistry, and innovation. Bird forms and distinctive notching connect the waka to Moriori carving traditions seen across rākau momori, whare, and miheke.

Only part of the waka has been excavated so far. Moriori have stepped forward to support the next phase, ensuring the waka is carefully excavated and protected in line with tikane Moriori.

The story of this waka is still unfolding, continuing to reveal our history, presence and relationship with our henu, moana, karāpuna and hokopapa.

The ancient waka (canoe) discovered in 2024 at the mouth of the Rangihoua Stream on the northern coast of Rēkohu (Chatham Islands) strongly supports what Moriori have always known. This waka miheke is a sacred and physical connection between our karāpuna (ancestors) and Moriori today.

The waka embodies Moriori voyaging knowledge, cultural continuity and enduring relationships with the moana and henu. It carries our history and traditions forward for future generations and affirms Moriori oral histories of early ocean voyaging, settlement and adaptation on Rēkohu and Rangihaute, independent of later colonial narratives.

The Rangihoua Waka stands as a miheke in its own right, grounded in Moriori knowledge systems and tikane.

A public blessing of the waka site, held by local imi and iwi.

Location of the Discovery

The Rangihoua Waka was discovered at site CH744, located at the mouth of the Rangihoua Stream within a coastal area called Tē Tūtaitei Awanui. This area forms part of a wider, continuous Moriori archaeological and cultural landscape referred to as Site 100.

The landscape includes whare sites, shell middens, food preparation areas, and several kōimi or wāhi tchap’ (burial or sacred places). Because the area is so culturally important, this coastline was given a special statutory overlay protection for Moriori under the Moriori Claims Settlement Act 2021.

The presence of the waka within this protected cultural landscape reinforces its status as a miheke inextricably connected to Moriori arrival, ancestral occupation, and enduring relationship with this place.

Left: The Rangihoua Stream where the waka was discovered in 2024.

Right: Dani McQuarrie and Heidi Lanauze delicately removing sand from a fragment of the waka, guided by conservator Sara Gainsford.

Alignment with Moriori History

Moriori traditional knowledge records multiple migration waves that shaped our settlement history on Rēkohu and Rangihaute. These arrivals are preserved through oral histories, place names, and cultural memory and are increasingly supported by archaeological evidence.

The FIRST ARRIVALS

Our traditions hold that the earliest karāpuna, led by Rongomaiwhenua and Rongomaitere, came directly to the islands from the Eastern/Central Pacific. These arrivals establish our rights as the waina pono (traditional inhabitants) of Rēkohu.

Moriori oral records place these first arrivals many centuries before the arrival of later waka migrations to Rēkohu, including the Rangimata and Rangihoua. These traditions underpin Moriori identity, authority, and enduring relationships with the henu and moana.

THE SECOND ARRIVALS

Many years later, approximately 29 generations (according to Maikoua), Kahu arrived on Rēkohu. After failing to cultivate crops, Kahu and his people left Rēkohu, though some may have remained (Shand, 1894).

THE RANGIMATA AND RANGIHOUA VOYAGES

A later migration involved two large, double-hulled waka, the Rangimata and Rangihoua, which departed Hhiawaiki (Hawaiki) to escape ongoing conflict. The arrival of these waka marked the end of the Ko Matangi Ao period (ancient knowledge brought with them from Hhiawaiki) and the beginning of Hokorong’ Tīring’ (the time of the 'Hearing of the Ears' which post-dates the arrival at Rēkohu).

Traditional accounts state that the Rangihoua was ill-prepared and unfinished when it left, and was swiftly smashed up by rough winds upon reaching the northern coast. This wreckage occurred near or on the site where the CH744 vessel was located.

Radiocarbon dating of a short-lived fibre sample provides a strong time context for the waka. The majority of the dated fibres indicate a growth date around 1440–1470 AD (Maxwell, 2025, para 151). However, it is crucial to note that almost all the dated materials, including fibres, cordage, and rope, are short-lived materials that would have been replaced throughout the life of the vessel (Maxwell, 2025, para 152).

These findings align with Moriori traditions that place the arrival of Rangimata and the wrecking of Rangihoua at approximately 800 years ago.

THE OROPUKE ARRIVAL

A further waka, Oropuke, arrived from Hhiawaiki approximately one generation later. This arrival aligns with Moriori traditions of voyaging connections and reinforces the sequence of Moriori migrations.

Left: Conservator Sara Gainsford removing sand from a recovered piece of the waka.

Right: A recovered section of the waka revealing its distinctive notched edges.

Scientific Evidence and Traditional Knowledge

Archaeological assessment and interim radiocarbon dating provides scientific validation for the Moriori accounts of ancestral settlement and waka technology.

Earlier material was also found during the excavation, including a piece of rope pre-dating 1415 AD, and a bottle gourd (the first known found on Rēkohu). The interim report indicates that the gourd may pre-date 1400 AD (Maxwell, 2025, para 151).

The Project Archaeologist has noted that the waka itself may be considerably older than the dates derived from these perishable associated materials (Maxwell, 2025, para 152). This scientific caveat supports the Moriori traditional knowledge that the waka may be over 800 years old.

Waka Technology and Moriori Artistry

Physical evidence from the excavation reveals unique construction and carving styles highly indicative of Moriori cultural provenance.

The tested timbers are identified as being of New Zealand origin. Based on the thickness of a triangular timber fragment (thought to be a stern or bow cover), va’a builder Heemi Eruera, drawing on traditional waka knowledge, has estimated that the vessel may have been at least 20 metres long. This size aligns with Moriori traditions of large voyaging waka capable of carrying up to 50 people.

The excavated components include elaborate carved timbers with inset obsidian discs.

Distinctive Moriori Design

The carvings and construction techniques feature motifs characteristic of Moriori artistic traditions.

Bird forms, often seen in rākau momori (tree engravings) and ceremonial items like the albatross-shaped patu hopo, are present. Long, slender bird-head pieces with distinctive notching have been recovered from the site.

Notching along the edges of wooden components is a salient feature of Moriori art, also seen on whare carvings and wooden miheke, carved waka prows and bone and stone tools. This technique was functional in securing bindings in waka construction, and possibly served as a material mnemonic device for reciting hokopapa (genealogy).

Images supplied by Heidi Lanauze

Cultural Significance

The discovery of the Rangihoua Waka at the mouth of the Rangihoua Stream affirms Moriori oral traditions. The place name itself carries this history, reflecting how Moriori karāpuna embedded memory within the landscape.

Archaeological science does not replace Moriori knowledge but supports and strengthens understanding that hokopapa and stories about our karāpuna accurately show Moriori voyaging, settlement and our long connection to Rēkohu and the land itself (for archaeological recording purposes, the site at which the Rangihoua Waka was located and documented is designated CH744).

The waka embodies Moriori innovation, resilience and tikane. It demonstrates that Moriori knowledge and science are not separate domains but interconnected ways of understanding our world. Modern archaeological science gives tangible form to what our ancestors have always known and which they passed down to their present day descendants.

Rangihoua Waka stands as enduring evidence of Moriori presence, rangatiratanga and relationship with Rēkohu that exists independently of later colonial processes.

Tikane Moriori and Rangatiratanga

For Moriori, the Rangihoua Waka is not simply an archaeological artefact but a miheke with its own cultural status and hokopapa. Under tikane Moriori, miheke are treated as taonga tuku iho that carry ancestral presence and responsibility.

Moriori have recognised cultural interests and responsibilities in relation to the waka under tikane Moriori and through the statutory cultural overlay that applies to this place. While the Crown retains interim legal and administrative responsibilities, Moriori involvement and values inform how the waka is approached, cared for, and protected.

Left: Larger pieces of the waka, carefully tagged and catalogued.

Right: Tchimirik Rosie Ryan assisting conservator Sara Gainsford with removing sand from a recovered piece of the waka.

Current Status

The Rangihoua Waka is located on land owned and administered by the Department of Conservation and, at this stage, the Crown holds prima facie ownership of the waka. Only part of the waka has been excavated to date.

The Crown has advised that it does not have funding available to complete the excavation. In response, Moriori have stepped forward to fund the next phase of work so that the waka can be carefully excavated, protected, and studied in accordance with professional standards and Moriori values.

Care, Protection, and Future Management

The long-term care of the Rangihoua Waka must address both physical preservation and cultural integrity.

For Moriori, appropriate care involves not only technical conservation measures, but also respect for the waka’s spiritual, historical, and relational dimensions. Preservation is understood not simply as preventing physical deterioration, but as maintaining the mana and cultural meaning of the miheke for present and future generations.

Future management of the waka should therefore be guided by Moriori values and cultural considerations, and undertaken in collaboration with the local community of Rēkohu, archaeologists, conservators, and other relevant specialists. This collaborative approach will support appropriate handling, storage, access, and interpretation, and includes consideration of where and how the waka is held, who may engage with it, and how knowledge associated with it is shared.

The Rangihoua Waka is located on land owned and administered by the Department of Conservation.

Puanga Taumaha Wānanga

In July, we hosted a two-day Puanga Taumaha wānanga in Ashburton, where attendees learned about the Moriori New Year and its significance within tikane Moriori. Participants were encouraged to plan their own meaningful New Year celebrations with their hūnau, weaving in these values alongside supporting rongo and karakī.

Attendees of the wānanga recite a karakī while holding kopi rākau they crafted during the previous day’s workshop, while a .breakfast of Rēkohu blue cod and shellfish steam on the open fire.

In July, we hosted a two-day Puanga Taumaha wānanga in Ashburton, where attendees learned about the Moriori New Year and its significance within tikane Moriori. Participants were encouraged to plan their own meaningful New Year celebrations with their hūnau, weaving in these values alongside supporting rongo and karakī.

Jessica Ashton (left) and Lisa Donaldson (right) carve tuwhatu from pungatei (pumice).

After a restful night, guests gathered at dawn to prepare a delicious kei ata (breakfast), cooked over an open fire as the stars faded. Alongside this, they unveiled pumice tuwhatu (carved figures) created during the previous day’s session. Traditionally, these figures represented etchu (deities) such as Pou and Tangaroa, who presided over fish. Participants also crafted kopi rakau — sticks to which kopi seeds were traditionally bound — an ancient practice described by Johann Friedrich Engst, who wrote: “Each person points the stick to Puanga and pronounces his speech of worship or supplication for a blessed fruitfulness of this tree.”

As part of our agreement with Te Mātāwai, who kindly funded this tchipangă, we will be delivering further taumaha wānanga before the end of the current financial year. We have also developed a series of Puanga resources, which will be shared with hūnau ahead of next year’s celebrations. Planning for these wānanga is underway, and we look forward to sharing details soon.

Taumaha to Tiriana Smith and Deborah Goomes for leading this kaupapa.

Supported by Te Mātāwai – Kia ūkaipō anō te reo.

Rongo Puanga Taumaha

Written by Tiriana Smith

Hokomenetai Puanga taumaha!

Ta hunau o ta rangi

Kioranga!

Puanga

Tautoru

Matariki

Ka whetu nawenewene

Wanui

Tukepipi

Ta hunau o ta rangi

Kioranga!

Hokomenetai Puanga taumaha!

In unity Puanga thanksgiving

The family of the heavens

Greetings!

Puanga

Tautoru

Matariki

Forgotten stars

Wanui

Tukepipi

The family of the heavens

Greetings!

In unity Puanga thanksgiving

You can listen to Puanga Taumaha here.

Repatriation of Kōimi T’chakat from Canberra

In March, Trustees Jared Watty and Belinda Williamson travelled to Canberra on behalf of HMT to take part in the profoundly moving repatriation of two kōimi tchakat’ Moriori (Moriori ancestral remains) from the National Museum of Australia. This moment marked not just the return of our karāpuna (ancestors), but another step in the continuing journey of reconnection and healing for our imi.

We are pleased to share a significant update regarding the recent repatriation of two Kōimi T’chakat Moriori from the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.

Left to right: Belinda Williamson, Jared Watty and Kiwa Hammond.

Photo courtesy of Jason McCarthy/National Museum of Australia.

Earlier this month, Jared Watty and Belinda Williamson, representing the Hokotehi Moriori Trust, travelled to Canberra to participate in this profoundly moving event.

A respectful and culturally sensitive repatriation ceremony began with a powerful water ceremony performed by the Ngunnawal people, who welcomed the Te Papa Tongarewa team and our trustees Jared Watty and Belinda Williamson to their land. A smoking ceremony led by the Ngambri people followed, which cleansed and honoured the kōimi t’chakat Moriori during the formal handover.

We were honoured to accompany a dedicated team from Te Papa, including Dr Te Herekiekie Herewini, Dr Arapata Hakiwai, Kiwa Hammond, and Hinerangi Edwards. Their expertise and cultural knowledge were invaluable throughout the process.

The Kōimi T’chakat Moriori are now safely housed in the Whatu Tchap at Te Papa in Wellington, where they will remain until their final journey home to Rēkohu and Rangihaute. A small, intimate ceremony was held at Te Papa to mark their safe arrival.

This repatriation is a significant step in our ongoing efforts to reclaim and honour our ancestral heritage. We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the National Museum of Australia, the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, Te Papa, and all those who contributed to the successful return of our karāpuna.

We will inform you of developments regarding the eventual return of our karāpuna to their ancestral homeland.

Hokotehi Moriori Trust joins New Zealand’s pledge to the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge

Hokotehi Moriori Trust joins New Zealand’s pledge to the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge.

We are pleased to announce that Rēkohu has been included in the prestigious Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC), joining Rakiura and Maukahuka as part of a global network of islands dedicated to ecological restoration by 2030. This inclusion provides us with the invaluable opportunity to collaborate with international experts and donors, enabling us to advance our long-term vision for restoring our islands. We are working towards a sustainable future for Rēkohu and the broader global community by participating in this challenge.

Rēkohu is a haven for native birds and plants found nowhere else, including the karure/Chatham Island black robin, Chatham Island tāiko/magenta petrel, and Chatham Island albatross/hopo. We have the opportunity to make a real impact on biodiversity and ocean health. By investing in these projects, we are contributing to our planet’s well-being and future and helping restore ecosystems, support the Predator Free 2050 initiative, and ensure a sustainable future for generations to come, fostering a healthier environment for all.

The IOCC pledge is to continue removing feral cats from Rangihaute and complete the first phase of the Predator Free project on Rēkohu by removing possums and feral cats. The long-term goal is to remove possums, feral cats, and rats from the archipelago and see the seabird-driven ecosystem thriving. This community-driven project is led by the Chatham Islands Landscape Restoration Trust, with the Hokotehi Moriori Trust and Ngāti Mutunga o Wharekauri. It is supported by the Department of Conservation, Chatham Islands Council, and Predator Free 2050 Ltd.

Recently, representatives from the Hokotehi Moriori Trust, Ngāti Mutunga o Wharekauri Iwi Trust, and the Chatham Island Landscape Restoration Trust travelled to Bluff to launch and sign the pledge with our IOCC partners. During our visit, we also had the opportunity to meet with organisations such as Re:wild and Island Conservation, where we discussed our shared goals for restoring Rēkohu and Rangihaute. Our heartfelt gratitude goes to the whānau at Te Runaka o Awarua for their manawareka/warm hospitality during our visit.

PUANGA (MORIORI NEW YEAR) CELEBRATIONS

What a week of celebrations our Puanga festivities were!

What a week of celebrations our Puanga festivities were! We enjoyed sharing our knowledge of this kaupapa with all those who came through the doors of Kōpinga over the week for the various activities we had, whether it was the beautiful feast put on by T'Chieki Marae, Loretta Lanauze, the hūnau who contributed to our communal mural, the crafty mahine who whipped up healing rongoa in the kitchen, the t'chimirik who entered our colouring competition, our hūnau who came to connect with our trustees at our consultation huinga or our hūnau from afar who joined in the fun with our digital resources.

We would especially like to thank Te Puni Kōkiri, whose support made this week of festivities possible.

KAINGAROA KICK-OFF | COMMUNITY PLANTING DAY

In just a few hours, 700 plants (a mixture of native and endemic species) were planted.

To celebrate the launch of the Predator-Free Chathams programme, we held a community planting day on Friday, July 19, where Rēkohu locals helped to restore Kaingaroa's natural landscape with native and endemic plant species and learnt about local efforts to restore the island's natural landscape.

In just a few hours, 700 plants (a mixture of native and endemic species) were planted. We loved seeing our tchimirik getting stuck in, as they will be able to reap the rewards of this mahi for years to come.

This event was a collaboration between Hokotehi Moriori Trust, Chatham Islands Landscapes Restoration Trust and the Department of Conservation.

UPLIFT OF RAUTINI

After careful planning between Hokotehi Moriori Trust, Ngati Mutunga o Wharekauri, Moriori Imi Settlement Trust and the Department of Conservation (DoC), the excavation of rongomoana 'Rautini' began on July 9.

After careful planning between Hokotehi Moriori Trust, Ngati Mutunga o Wharekauri, Moriori Imi Settlement Trust and the Department of Conservation (DoC), the excavation of rongomoana 'Rautini' began on July 9.

Hūnau were invited to join us in Te One for karakī and shared breakfast before breaking the ground, and many joined us over the week to wash down bones and scrub the teeth of the whale.

Rautini is now safely stowed in storage until the next stage in this kaupapa begins. A huge taumaha to all our hūnau who helped to make this uplift possible, whale expert whaea Rāmari Stewart and her team from the mainland for sharing their invaluable knowledge with us, and Tiriana Smith and the extended DoC hūnau who have been essential to the success of this kaupapa

Repatriation of Koimi Tchakat

In March 2025, Trustees Jared Watty and Belinda Williamson travelled to Canberra on behalf of HMT to take part in the profoundly moving repatriation of two kōimi tchakat’ Moriori (Moriori ancestral remains) from the National Museum of Australia.

A pōwhiri for the largest return of kōimi tchakat held at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in 2022.

The remains of 111 Moriori and two Maori karāpuna were returned from London’s Natural History Museum.

Credit: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewera.

One of the most important projects for our imi is the return of kōimi tchakat (ancestral remains), which were once unceremoniously dug up to be traded as curiosities and, for up to 100 years since, have sat in collections overseas and across Aotearoa.

This mahi is the result over over a decade of research and negotiations, and while this work is ongoing, the remains of over 100 Moriori karāpuna have been returned so far. The remains are being temporarily held in a wāhi tapu – a sacred resting site – at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, before they will taken back to their rightful resting place on Rēkohu.

Hou Rongo: Moriori, Music and Manawa

In a marriage of ancient wisdom and cutting-edge technology, Hokotehi Moriori Trust partnered with a research team from the University of Otago to create an immersive, multi-sensory exhibition – the result of a two-year groundbreaking project to illuminate the cultural vibrance of Moriori people.

OPEN NOW

Nelson Provincial Museum Pupuri Taonga o Te Tai Ao

Date: 3 December 2025 - 1 March 2026

Price: Free for Nelson Tasman residents.

In a marriage of ancient wisdom and cutting-edge technology, Hokotehi Moriori Trust partnered with a research team from the University of Otago to create an immersive, multi-sensory exhibition – the result of a two-year groundbreaking project to illuminate the cultural vibrance of Moriori people.

The Hou Rongo exhibition was co-designed to combine Totohungatanga Moriori with innovative technology to support cultural revitalisation of New Zealand’s indigenous Moriori people of Rēkohu (Chatham Islands) and is supported by a team of scientists, musicians and media artists from Rēkohu and abroad.

The strong connection between ta imi Moriori and the natural world are brought into the modern world with film, photogrammetry, sound-design and scent reconstruction. 3D-printed replicas of the only two known historic Moriori flutes have been created, allowing visitors the opportunity to handle objects that would otherwise be unavailable.

The strong connection between ta imi Moriori and the natural world are brought into the modern world with film, photogrammetry, sound-design and scent reconstruction. 3D-printed replicas of the only two known historic Moriori flutes have been created, allowing visitors the opportunity to handle objects that would otherwise be unavailable.

Large video projections, paired with an immersive soundscape offer an ambient sense of place, evoking the feeling of being on Rēkohu amid the realms of the etchu (deities). A physical representation of the pou at Kōpinga marae displays Moriori iconography and features a video of the Karakii Rangitokona, the Moriori Creation Story, spoken in ta rē Moriori.

Visitors to the exhibition can immerse themselves the vibrance of Moriori culture through multi-sensory activities utilising physical, digital and extended reality components while enjoying rongo (songs), stories and hands-on wānanga (workshops).

Preservation of Rakau Momori

In March, Te Papa conservator Nirmala Balram returned to Rēkohu with imi member Bella Penter to further treat the rākau momori housed within the Kōpinga grounds. During their visit, stages one and two of an ongoing conservation plan were completed, with the assistance of on-island volunteers.

In March, Te Papa conservator Nirmala Balram returned to Rēkohu with imi member Bella Penter to further treat the rākau momori housed within the Kōpinga grounds. During their visit, stages one and two of an ongoing conservation plan were completed, with the assistance of on-island volunteers.

Nirmala and Bella last visited in September 2023, when condition reports, measurements, images and general descriptions were completed for each of the stored rākau momori. Since then, continued observation, borer treatment and biocide spraying have seen insect infestations eradicated.

The conservation focus of the most recent visit was to stabilise the dry rot and disintegrating parts of the rākau momori. Resin and synthetic wood glue were applied, and the trees were carefully bandaged to align loose elements to the base and minimise future loss.

“The focus is for the physical preservation of the harvested trunks to ensure the intangible links can be maintained for the present and future generations,” said Nirmala.

Of the 29 trees removed between 2010 and 2015, the majority are from Hāpūpū, with one each from Taia, Kairae and Pehenui. In order to fill in the gaps of what can and cannot be seen today, imagery from previous research initiatives is being consulted to gain a clearer understanding of what each tree might once have represented.

The next step in the conservation plan is developing a stable, humidity-controlled environment for the 29 rākau momori. This will halt their deterioration and make future conservation efforts easier. Plans for this miheke whare are underway.